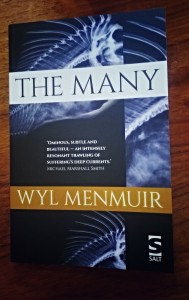

Author: Wyl Menmuir

Finished on: 16 June 2016

Where did I get this book: I bought it (I know, I know…) following an irresistible recommendation from a friend

I don’t know Wyl Menmuir, but his sister-in-law is my friend. When people ‘in real life’ write a book and have it published, this is like some kind of crazy magic to me. It is possible. Someone that I know for sure is a real person has done this. So maybe I can too. I think that’s the rationale going on anyway when I throw the book-buying ban out of the window and order a copy straight away. (Although it did make me laugh that I bought this at the same time as Shirley Conran’s Savages from Wordery, so as a new writer of this very serious book, Menmuir’s ‘people who liked this also bought’ will be screwed. Sorry.)

It would also have been rather awkward if I’d had to go back to my friend and tell her that I thought her brother-in-law’s book that she’d recommended so highly was rubbish.

But this book is not rubbish. This book is extraordinary. I would go so far as to say I loved it.

The story is told in a gentle, understated style. For someone a little bit obsessed with Robert Louis Stevenson at the moment, this was a huge change in tone for me. There are no sword fights; there is no buried treasure (except maybe sanity); there is very little drama. But the writing is beautiful, and Menmuir succeeds spectacularly well in endowing everything with several levels of meaning, without it seeming forced or self-conscious.

The house has not been cleared, the agent had said to him from behind a wide expanse of desk, and the words come back to him as he lies back in the bath. Timothy gets out of the bath quickly and wraps a towel around himself, and not bothering to dry off, he goes down to the kitchen. With a growing puddle of water gathering around his feet, he stands in front of the kitchen units and takes the handles of the cupboards nearest to him in both hands, opening both units simultaneously. There is the briefest moment in which he feels the open cupboards retain their darkness for a fraction longer than they should before they allow the light in.

On the surface, the story is a cross between The Wicker Man and *searches for a book or film about mutant fish, and fails to find one*. Our protagonist Timothy is a newcomer to an excessively insular seaside community that he and his wife had visited once early on in their relationship. The village life revolves around fishing, but that trade has been decimated by the presence of poisons in the water. When the fishermen do manage a catch, the whole lot is always purchased by a mysterious lady in a grey coat. There is one fisherman, Ethan, who is moved by Timothy’s presence in the village more than any other – at first reluctant to make contact, but then seeking him out and deliberately spending time together. Menmuir splits our perspective on the story between these two men.

But beneath the surface, this is a book about death. Or rather, the impact that death has on the living. We know from the beginning of the story that Ethan’s interest stems from the fact that Timothy has moved into the house of a dead man/ boy named Perran, someone who meant a great deal to Ethan.

I almost want to write two reviews of this book – one for those who haven’t, and one for those who have read it. Because it is so laden with symbolism that reading the end becomes a delicious ‘what does this mean, what does that mean?’ process. And I know from reading others that I have had a different interpretation from at least one other reviewer.

In my version of The Many we meet god, and a man so broken that his world is poisoned, and its very fabric falling apart. But this is ultimately a story of healing, and how it is possible to put the pieces back together – even if it takes an extreme journey and some severe mental ill-health to get us there.

But it is entirely possible you will experience something completely different.

This book is highly recommended – go and get yourself a copy, read it and then tell me what you think it all means. And maybe when it has become the runaway success it deserves to be, and everyone has read it, I will write another review about what it all meant to me.

Great review. I just loved this book. I know what you mean about the ending. It’s so delightfully, almost perversely ambiguous isn’t it?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not sure if this would be one for me. it would have been really awkward wouldn’t it if you had thoroughly disliked it

LikeLike

I haven’t read it, I came here intrigued by BookerTalk’s review and your comment there.

Could the woman in grey be an anonymous bureaucrat from the EU?

LikeLike

[…] did I get this book: Lent to me as an “If you liked The Many you might like this…” […]

LikeLike

[…] The Many by Wyl Menmuir […]

LikeLike

[…] published by the brilliant Salt – the previous books I’ve read from them, Nutcase and The Many, having been two of the most impressive books I’ve read in years. It would be fair to say I […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Fires is the follow up to Menmuir’s extraordinary Booker-longlisted debut novel The Many, a stunning book and a tough act to beat. In Fox Fires, Menmuir has written a fascinating and […]

LikeLike